The Legend of the Undercut: A Modern F1 Fairy Tale

If you’ve spent any time in the company of modern Formula 1 strategists, you’ll know the undercut is spoken of with the reverence usually reserved for holy relics or Fernando Alonso’s eyebrows. The theory is simple: pit before your rival, use fresh tyres to set a blistering lap, and leapfrog them when they pit a lap later. It’s the tactical equivalent of stealing someone’s lunch while they’re still queuing for the canteen.

- The Legend of the Undercut: A Modern F1 Fairy Tale

- Imola 2005: The Stage Is Set

- The Anatomy of the Race: Strategy, Tyres, and the Art of Defence

- The Final Stint: A Masterclass in Defence

- Why the Undercut Didn’t Matter

- The Historical Parallels: When Strategy Fails, Drivers Prevail

- The Modern Obsession: Why We Still Worship the Undercut

- The Numbers: A Statistical Postscript

- Waste a Bit More Time

But as with most things in Formula 1, reality is a little more complicated. And nowhere is this more evident than in the 2005 San Marino Grand Prix at Imola, where Fernando Alonso and Michael Schumacher staged a duel so intense that it’s still being dissected two decades later. The undercut? It was there, lurking in the background, but it was not the star of the show.

Let’s revisit that Sunday in April 2005, when the myth of the undercut was exposed by two drivers at the peak of their powers—and a Renault that simply refused to yield.

Imola 2005: The Stage Is Set

By the time the F1 circus rolled into Imola for round four of the 2005 season, the world had already noticed that Ferrari’s iron grip on the sport was slipping. The new rules—most notably the ban on tyre changes during the race—had kneecapped Bridgestone and, by extension, Ferrari. Renault, with Michelin tyres and a young, audacious Spaniard at the wheel, had seized the initiative.

Alonso arrived at Imola leading the championship, having won the previous two races. Schumacher, meanwhile, was desperate to remind everyone that he was still the reigning king. The scene was set for a classic, and the script did not disappoint.

The Anatomy of the Race: Strategy, Tyres, and the Art of Defence

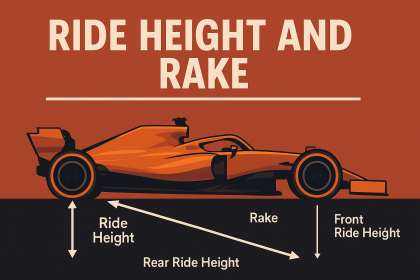

The 2005 San Marino Grand Prix was not won in the pit lane. It was won on the track, in a relentless, nerve-shredding 12-lap chase that saw Schumacher’s Ferrari glued to the rear wing of Alonso’s Renault. The undercut, that beloved weapon of modern strategists, was rendered impotent by a combination of regulations, tyre performance, and sheer bloody-mindedness.

Let’s break down why.

Tyre Rules: The Great Equaliser

In 2005, drivers had to complete the entire race on a single set of tyres. No fresh rubber after every pit stop. No “let’s try the softs and see what happens.” This rule, designed to cut costs and spice up the show, had the unintended consequence of making the undercut almost irrelevant. Pitting early meant risking catastrophic tyre degradation in the closing laps—a gamble few were willing to take.

As Rubens Barrichello, Schumacher’s teammate, put it at the time:

Rubens Barrichello, said:

All the overtaking taking place this year is more to do with the tyres than the actual DRS. The DRS only comes into play because of the tyres.

Of course, DRS was still a twinkle in Charlie Whiting’s eye in 2005, but the point stands: tyres, not pit stops, were the decisive factor.

The Pit Stops: A Red Herring

Both Alonso and Schumacher made two pit stops, as was customary in the refuelling era. But with no tyre changes, the stops were dictated by fuel strategy, not by the pursuit of fresh rubber. The undercut, in its modern sense, simply didn’t exist.

Schumacher’s second stop came on lap 50, one lap after Alonso’s. Theoretically, this gave Schumacher the chance to use his lighter car to set a “hammer time” lap and leapfrog Alonso. In practice, it made no difference. Alonso’s Renault was quick enough, and his out-lap was tidy enough, to maintain track position.

The Final Stint: A Masterclass in Defence

What followed was one of the most intense defensive drives in Formula 1 history. For 12 laps, Schumacher—arguably the greatest attacker the sport has ever seen—threw everything at Alonso. The Renault squirmed, twitched, and danced through Imola’s chicanes, but Alonso never put a wheel wrong.

As Alonso himself recalled years later:

Fernando Alonso recalled:

I was pushing every lap, every corner, every braking point. I knew if I made one mistake, Michael would be there.

Schumacher, for his part, was magnanimous in defeat:

Michael Schumacher said:

I tried everything I could, but Fernando didn’t make a single mistake. He deserved the win.

The gap at the flag? 0.215 seconds. The undercut? Nowhere to be seen.

Watch Alonso and Will Buxton relive the battle on F1.com

Why the Undercut Didn’t Matter

So why, in this most celebrated of modern F1 duels, did the undercut fail to materialise as a decisive factor?

1. Tyre Conservation Trumped All

With no tyre changes allowed, pitting early was a recipe for disaster. The final laps would have been a slow-motion car crash, with worn Michelins or Bridgestones turning to jelly. Both teams knew it, and so did the drivers.

2. Track Position Was King

Imola, with its narrow layout and limited overtaking opportunities, has always rewarded track position. Once Alonso emerged from his final stop ahead, Schumacher’s only hope was to force a mistake. The pit wall could do nothing but watch.

3. The Human Element

No amount of strategy can compensate for a driver who refuses to yield. Alonso’s defence was a masterclass in precision and composure. Schumacher’s attack was relentless but ultimately futile. The race was decided by skill, not spreadsheets.

The Historical Parallels: When Strategy Fails, Drivers Prevail

Imola 2005 was not the first time the undercut—or its ancestor, the “overcut”—was rendered irrelevant by circumstances. Think back to Monaco 1992, when Nigel Mansell, on fresh tyres, spent seven laps staring at the rear wing of Ayrton Senna’s McLaren. Or Hungary 1998, when Michael Schumacher himself executed a three-stop strategy so audacious that even Ross Brawn needed a lie down afterwards.

But in each case, the decisive factor was not pit stop timing, but the ability of one driver to withstand the pressure of another. The myth of the undercut is that it can always deliver victory. The reality is that, sometimes, you just have to drive.

The Modern Obsession: Why We Still Worship the Undercut

In today’s Formula 1, the undercut is back in vogue, thanks to high-degradation tyres, DRS, and the ever-present spectre of “dirty air.” Teams spend millions on simulation software, all in pursuit of the perfect pit window. But as Imola 2005 reminds us, strategy is only as good as the driver executing it.

As I’ve said before:

DRS doesn’t make you brave, it makes you pass.

And the undercut doesn’t make you a winner. Sometimes, it’s just a footnote.

The Numbers: A Statistical Postscript

For the data-obsessed among you (and I know you’re out there), here are the key stats from Imola 2005:

- Alonso’s final stint: 12 laps under constant pressure, average lap time within 0.2s of Schumacher

- Schumacher’s fastest lap: 1:21.858 (lap 49), set just before his final stop

- Alonso’s fastest lap: 1:22.203 (lap 50), his out-lap after the final stop

- Final gap: 0.215 seconds

No amount of pit stop wizardry could have changed the outcome. The race was won—and lost—on the track.

Waste a Bit More Time

For those who wish to dive deeper into the myth, the legend, and the reality of Imola 2005, here’s your homework:

- Alonso watches back his epic battle with Schumacher in Imola 2005 (Formula1.com)

- Why Alonso LOVES UNDERSTEER (YouTube)

- F1 2005 R4 San Marino – Alonso vs Schumacher (YouTube)

- RaceFans: After 50 races, DRS is killing my passion for F1

And if you’re still convinced the undercut is the answer to all of life’s problems, I have a bridge in Maranello to sell you.