The Art of Stopping: From Leather Shoes to Carbon Magic

If you were to pluck a Formula 1 driver from the grid of 1975—say, Niki Lauda, James Hunt, or Jody Scheckter—and drop him into a 2025 cockpit, the first thing to send him scrambling for the nearest exit wouldn’t be the hybrid power units, the labyrinthine steering wheels, or even the omnipresent data engineers.

- The Art of Stopping: From Leather Shoes to Carbon Magic

- 1975: When Braking Was a Negotiation

- 2025: The Era of Carbon, Ceramics, and Computer Control

- The Science of Stopping: A Statistical Chasm

- Brake-by-Wire: The Invisible Hand

- The Human Factor: Physiology Meets Physics

- Safety: The Unspoken Revolution

- The Psychological Shock: From Margin to Maximum

- What If? The 1975 Driver in a 2025 Car

- Waste a bit more time

No, it would be the brakes. Not the speed, but the violence with which modern F1 cars shed it. In 1975, the bravest men in motorsport trusted their lives to steel discs, asbestos pads, and a prayer. Today, the only thing more advanced than the brakes themselves is the telemetry that tells you exactly how much you’re underusing them. The difference is not just technological—it’s philosophical, anatomical, and, for a 1975 driver, downright terrifying.

1975: When Braking Was a Negotiation

Let’s set the scene. The Ferrari 312T, the McLaren M23, the Tyrrell 007—these were the chariots of the day. Brakes were steel discs, often ventilated if you were lucky, and pads made from materials that would give a modern health and safety officer a coronary. Cooling was a matter of ducting and hope. Brake fade was not a possibility; it was an inevitability.

Drivers learned to “nurse” their brakes, feathering the pedal, pumping it to keep pressure, and always—always—leaving a margin for the unknown. The phrase “brake by feel” was literal: you felt the pedal go soft, you felt the car squirm, and you felt your heart rate spike as you prayed the car would slow before the Armco did the job for you.

As Maurice Hamilton wrote of the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuïc, “the weekend of the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix was one of the most terrifying I’ve ever experienced.” Read more

Jackie Stewart, three-time World Champion:

If you lost the brakes, you lost the car. And sometimes, you lost more than that.

2025: The Era of Carbon, Ceramics, and Computer Control

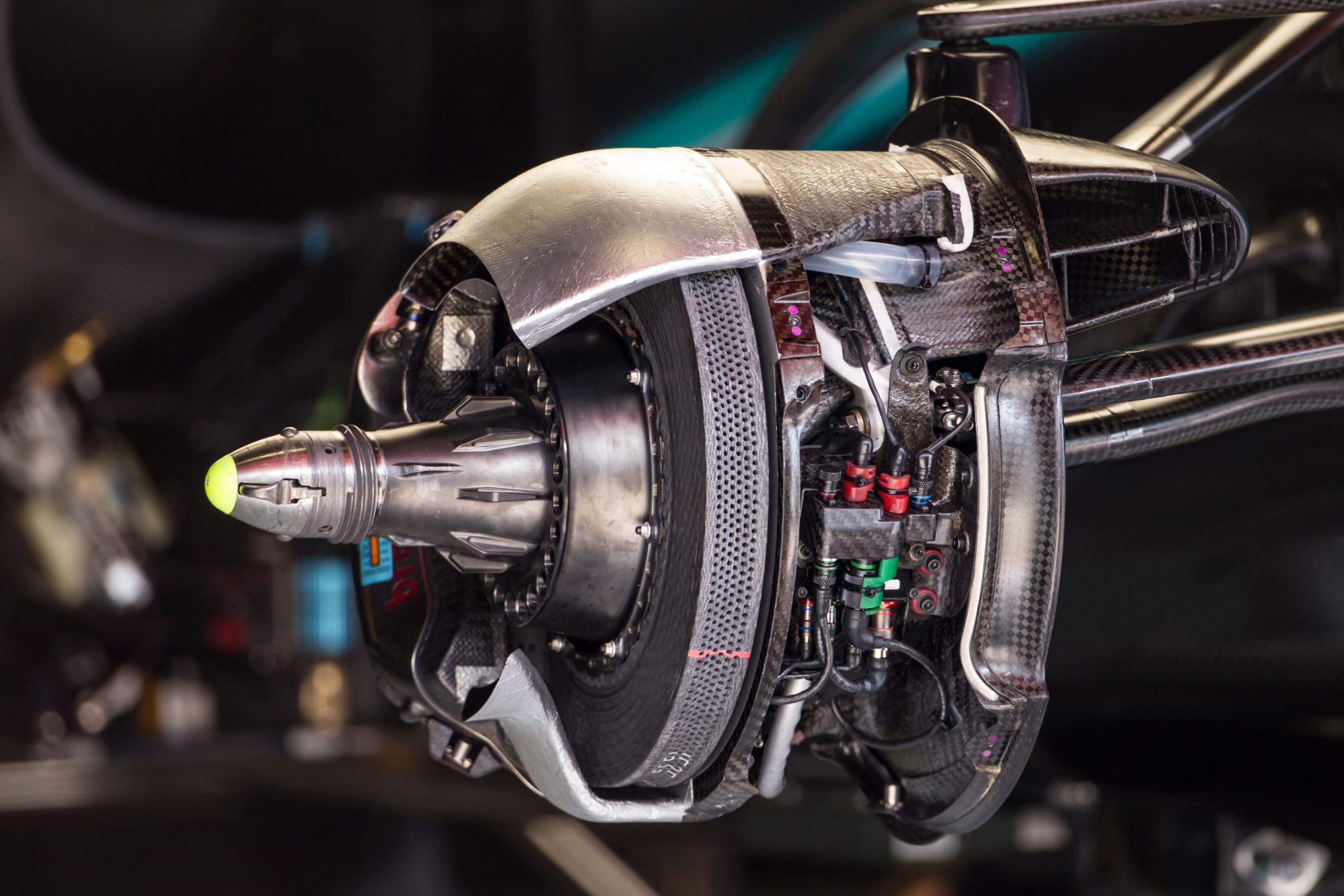

Fast forward to today. The 2025 Formula 1 car is a spaceship with wheels, and nowhere is this more evident than in the braking system. Carbon-carbon discs, carbon pads, brake-by-wire rear systems, and regenerative braking that feeds energy back into the battery. The pedal is connected to a computer, which is connected to a hydraulic system, which is connected to a set of discs that operate at temperatures hotter than a pizza oven.

The numbers are absurd. From 330 km/h to 80 km/h in less than 2 seconds, covering just 65 metres. Peak deceleration of over 6g—enough to make your eyeballs consider a career change. The pedal force required is calibrated to the gram, and the system is so reliable that “brake fade” is a phrase reserved for vintage car rallies.

Charles Leclerc, Ferrari, 2025:

I hit the brakes at 100 metres, and the car just stops. It’s like hitting a wall, but you’re in control. I can’t imagine doing this with steel discs.

The Science of Stopping: A Statistical Chasm

Let’s talk numbers, because numbers don’t lie (unlike some team principals I could mention). In 1975, the average deceleration under heavy braking was around 1.5g to 2g. Brake distances from 300 km/h to 100 km/h? About 180 metres, if you were lucky and the brakes were fresh.

In 2025, the same deceleration is over 6g, and the distance is slashed to less than 70 metres. That’s not evolution; that’s a quantum leap. The carbon-carbon discs can operate at over 1,000°C, and the pads are so aggressive they’d eat through a 1975 disc before the first pit stop.

A 1975 driver would find the pedal feel alien, the response instantaneous, and the physical forces overwhelming. The first time he hit the brakes at the end of the main straight, he’d either stall the engine, spin the car, or simply pass out.

Watch: The 1975 Spanish Grand Prix Disaster

Brake-by-Wire: The Invisible Hand

Perhaps the most mind-bending aspect for a 1975 driver would be brake-by-wire. In 2025, the rear brakes are not directly connected to the pedal. Instead, a computer decides how much braking force to apply to the rear wheels, balancing it with the energy recovery system (ERS) to maximize both stopping power and battery recharge.

This means the driver’s input is interpreted, not transmitted. For a driver used to feeling every vibration through a steel rod, this would be like playing a piano with oven mitts—except the piano is on fire and moving at 300 km/h.

Pedro Ivanov, Formula 1 BG:

Back in my day, we had gear sticks, not marketing departments. And when you hit the brakes, you knew exactly what was happening—or not happening.

The Human Factor: Physiology Meets Physics

Let’s not forget the human body. In 1975, drivers were athletes, yes, but the physical demands were different. Braking at 2g is one thing; braking at 6g is another. Modern F1 drivers train their necks, legs, and core to withstand forces that would make a fighter pilot wince.

A 1975 driver, unaccustomed to these loads, would struggle to keep his head upright, let alone modulate the brake pedal with the precision required. After a single lap, he’d be searching for the nearest oxygen mask and a strong drink.

Safety: The Unspoken Revolution

It’s easy to romanticize the past, but let’s be clear: the advances in braking technology have saved lives. In 1975, brake failure was a leading cause of accidents. Today, it’s almost unheard of. The reliability of modern systems means drivers can push to the limit, lap after lap, without fear of catastrophic failure.

As the Livemint article notes, “F1 has never been safer—that, though, being a relative word—than it is now.” The share of retirements due to technical reasons, including brakes, has plummeted from over 25% in the 1970s to under 10% today.

The Psychological Shock: From Margin to Maximum

For a 1975 driver, the biggest shock would not be the technology itself, but the mindset it enables. In the old days, you left a margin. You braked early, you managed your equipment, and you hoped for the best. In 2025, you brake at the last possible moment, every lap, every corner, knowing the system will deliver.

This is not just a change in technique; it’s a change in philosophy. The modern driver trusts the car in a way that would seem reckless—insane, even—to his 1975 counterpart.

Pedro Ivanov, Formula 1 BG:

Let’s wait for the third race before calling anyone a legend.

What If? The 1975 Driver in a 2025 Car

Let’s indulge in a thought experiment. Drop James Hunt into a 2025 Mercedes at Monza. He approaches the first chicane at 340 km/h. His instincts tell him to brake at 200 metres. The engineer on the radio tells him, “No, James, 80 metres is fine.” He laughs, tries it, and either locks up, spins, or simply refuses.

The modern car would stop, but the driver’s brain might not. The violence of the deceleration, the lack of fade, the sheer confidence required—it’s a different world.

Watch: Modern F1 braking explained

The Legacy: From Survival to Supremacy

The evolution of F1 brakes is a microcosm of the sport itself: relentless, unforgiving, and always looking forward. The men of 1975 were heroes, no doubt, but they played a different game. Today’s drivers are astronauts in Nomex, and their trust in the machinery is absolute.

If you want to understand why, just look at the brakes. They are the unsung heroes of every lap, every overtake, every moment of glory. And for a driver from 1975, they would be the stuff of nightmares—and, perhaps, envy.